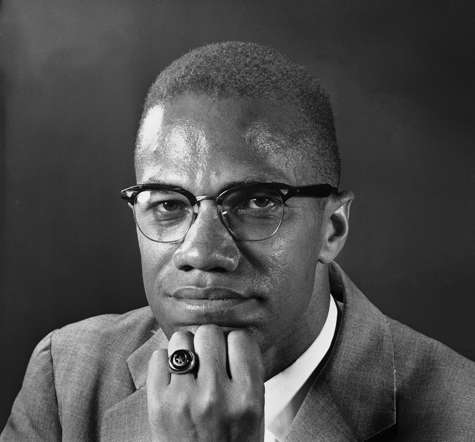

He was a complex man – so complex that even to call him Malcolm X is to present only a partial picture of him. In his 40 years he was Malcolm Little, the Harlem street hustler; then he was Malcolm X, the black civil rights spokesman for the Nation of Islam. And when he died he was El Hajj Malik El Shabazz, the convert to Sunni Islam.

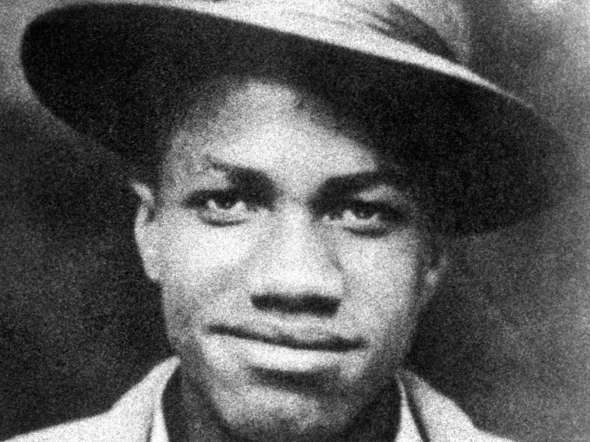

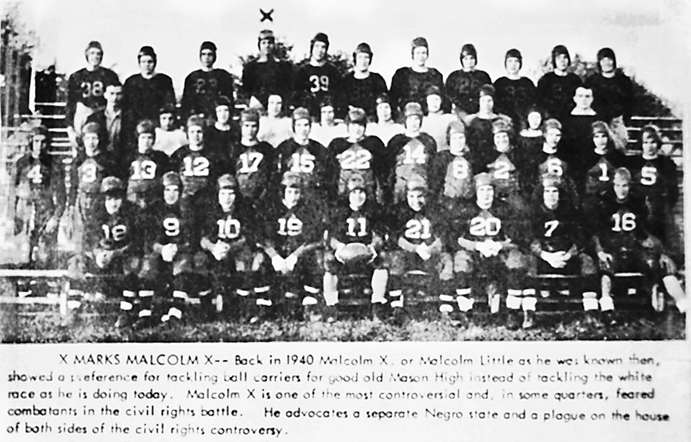

The man originally named Malcolm Little was born in Omaha, Nebraska, but his family soon moved north to escape the Ku Klux Klan

He was admirable in that even after he came to public prominence, he maintained his tendency to discard religious or political identities when newly acquired knowledge showed previously voiced beliefs to be ill-founded. It leaves us to wonder what other changes his curious mind might have undergone had he lived a longer life.

In 1992, the eponymous Spike Lee film introduced his story to newer generations. His well-known conversion in prison and his repudiation of his Western surname is in part responsible for the fact that Islam is the fastest growing religion among blacks in the UK.

Many black converts go on to practice Islam in a peaceful way but, others – as evidenced most dramatically in the cases of Germaine Lindsay, Richard Reid,Michael Adebowale, Michael Adeboloja and Brusthorn Ziamani – have other ideas.

The Islamist element of Malcolm X’s legacy mystifies many. Why, fifty years on, do so many disgruntled black people still opt for the dominant religion of the Middle East and North Africa? Why Islam rather than Buddhism or Hinduism? If a more self-reflecting religious identity is the aim, why not a faith that offers a black messiah – such as Rastafarianism?

In his popular autobiography, Malcolm X puts the Christian faith of most blacks in the US down to the "white, Christian slave master injecting his religion into this Negro." Later he states that "America needs to understand Islam because this is the one religion that erases from its society the race problem."

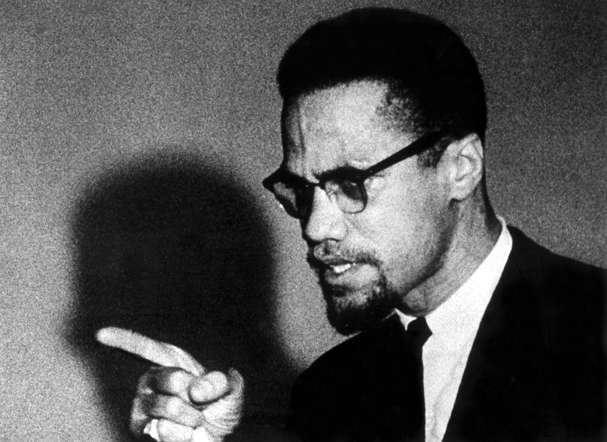

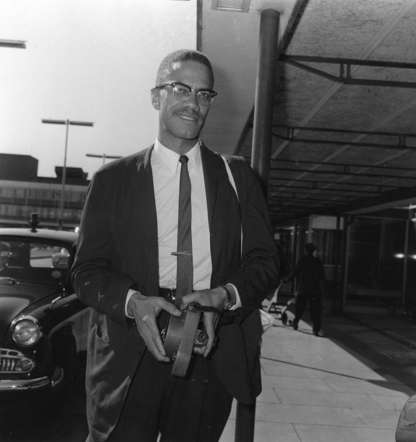

During a speech at the Urline Arena, Washington DC, in 1963 (Richard Saunders / Getty)

Given his acute sense of historical grievance, it is fair to assume that prior to his conversion to Sunni Islam, Malcolm X’s deprived upbringing and the parochial Western education available to most of us, would have made him unaware of historical facts such as the "Zanj" slave rebellion as far back as the 9th century – in Basra, in what is now modern day Iraq.

He would not have had access to the work of the 13th century writer, Ibn Battuta, and learned of the contempt in which even Islamic scholars held the black people of Africa, so apparent in their writings as they reported on the Islamic raiders venturing south as they had for centuries, in quest of young black women to rape and press into unpaid service as concubines and well-built black men to castrate and press into unpaid service as eunuch guards for their harems.

He would not have had the chance to learn that the idea of trading black slaves had in all likelihood been introduced to 16th century Europeans by Muslim slavers, who by then had a head start of almost a millennia in the ungodly practice.

If by the 1960s Malcolm X had been vexed at the glacial pace of improving race relations in the US, you wonder what he would have made of the fact that, when he set foot on Saudi Arabian soil for his Islamic holy pilgrimage in 1964, his Wahhabi hosts had only abolished slavery a mere couple of years earlier.

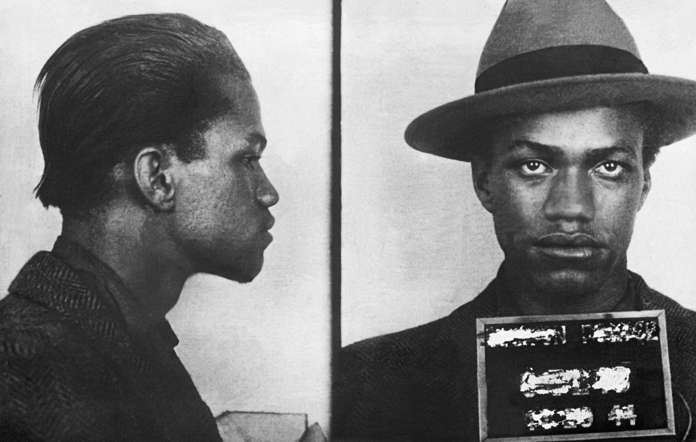

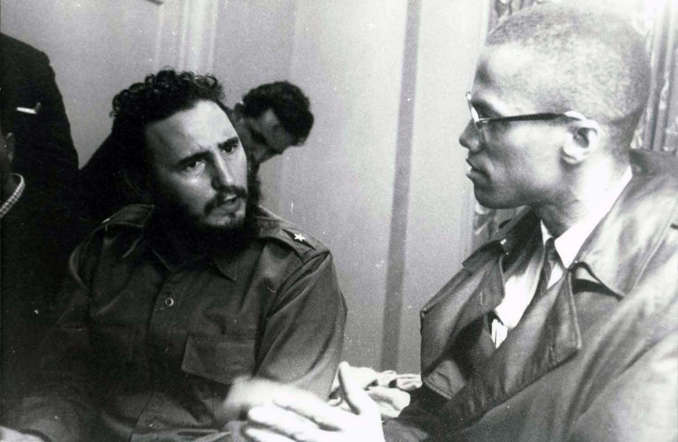

Thomas Hagan struggles with police after assassinating Malcolm X (AP)

Given his lifelong tendency towards intellectual self-refinement, it is fair to assume that Malcolm X might have made further alterations to his world view had he lived long enough to learn of these facts.

Fifty years on, a justice system that respects the dignity of all citizens will provide the best means to safeguard blacks from the anger that causes alienation and leads to what is now called Islamic radicalisation. But as we work towards this improved system, it would benefit blacks in temporary crisis to have a fuller and more accurate narrative in mind when faced with superficially plausible arguments by those seeking to enlist their disenchantment to their dubious causes.

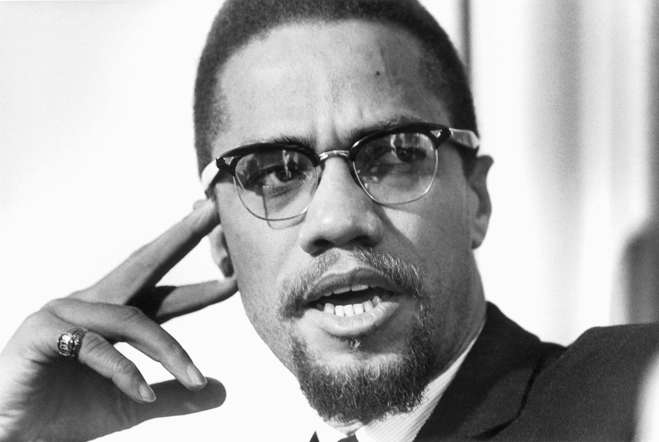

The man originally named Malcolm Little was born in Omaha, Nebraska, but his family soon moved north to escape the Ku Klux Klan

The man originally named Malcolm Little was born in Omaha, Nebraska, but his family soon moved north to escape the Ku Klux Klan

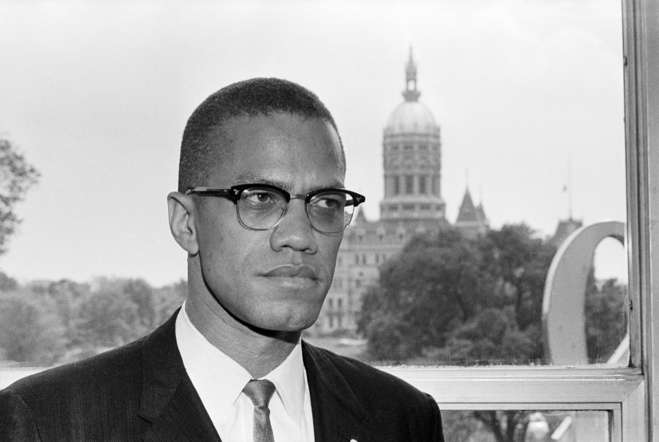

During a speech at the Urline Arena, Washington DC, in 1963 (Richard Saunders / Getty)

During a speech at the Urline Arena, Washington DC, in 1963 (Richard Saunders / Getty) Thomas Hagan struggles with police after assassinating Malcolm X (AP)

Thomas Hagan struggles with police after assassinating Malcolm X (AP)